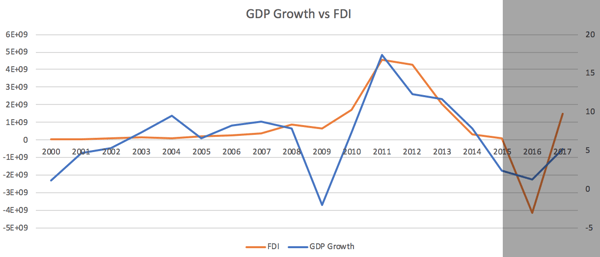

As any businessperson in Mongolia will tell you, the country’s economy is driven by mining and foreign investment. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is so important that the GDP growth has risen and fallen largely with the rise and fall of FDI. Even during the 2008 global financial crisis, GDP growth recovered fairly quickly because FDI did not drop too much.

|

| Source: World Bank and World Economic Outlook, IMF |

GDP growth dropped below zero only in 2009 and in 2010, quickly jumped back up to almost the 2008 growth rate. Then, in 2011, it reached a peak of 17.3%. Similarly, FDI dropped in 2009 and jumped to a peak in 2011. The fast recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis can be attributed to the 2009 Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement, which stated the terms for how Australia’s Rio Tinto and Canada’s Ivanhoe Mines would operate Oyu Tolgoi (OT) to benefit Mongolia.

Oyu Tolgoi is one of the world’s largest known deposits of copper and gold. The agreement began what is supposed to be at least 50 years of operation and investment into Mongolia. It not only started Rio Tinto’s private investment into Mongolia, which included educational and professional benefits for the community, but also build confidence in other investors. According to an entrepreneur with experience helping companies find foreign investment, during the boom brought by Oyu Tolgoi, large investment banks started looking at the Mongolian market.

Unfortunately, in the years after the 2011 peak, both FDI and GDP growth dropped. This is significant considering FDI had not dropped since 2005, except for a small drop in 2009, likely due to the global financial crisis. This can be attributed to a series of the Democratic Party’s government policies and actions that opposed foreign investment. For example, the government attempted to renegotiate the 2009 Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement. This conflict between OT and the government was driven by a populist movement against foreigners taking over control and resources in Mongolia.

In addition, in 2012, the government passed the Foreign Investments Law and the Strategic Entities Foreign Investments Law, which required government approval for large foreign investments. As the government started to interfere with Mongolian investments, foreign investors became more wary of allocating money to Mongolia.

|

| Source: World Bank |

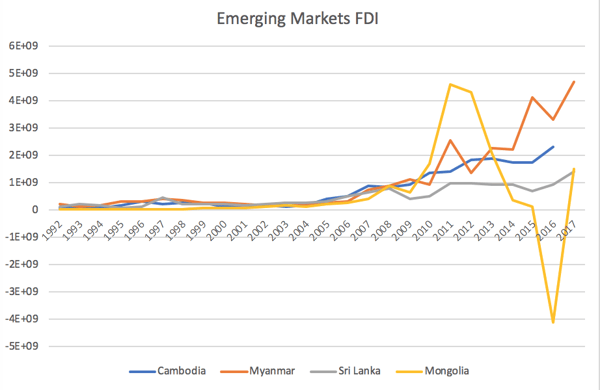

As the above graph shows, FDI surged as OT started its construction and operations, beating out FDI in many other emerging markets. However, as soon as the government revealed its populist position against foreign investment, FDI tanked, dropping farther than FDI in all the other emerging markets. In fact, foreign investors started pulling money out of the Mongolia economy.

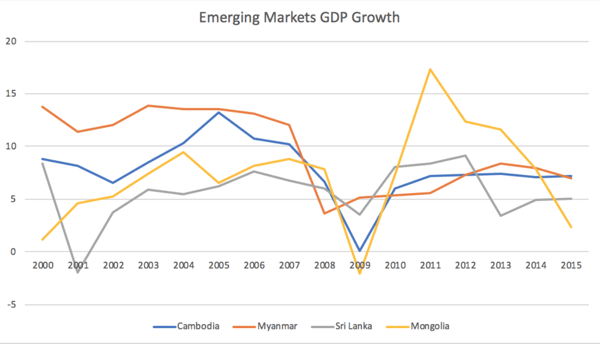

As expected, GDP growth dropped in Mongolia alongside FDI. It’s important to note that GDP growth in Mongolia dropped below growth in other emerging markets. In particular, the slowdown in FDI due to the government’s position put the Mongolian economy in a worse spot than Cambodia and Myanmar, two very popular emerging markets destination for frontier market funds. However, Mongolia’s economy grew much faster when Oyu Tolgoi and other part foreign operations in Mongolia were allowed to work without government interference.

|

| Source: World Economic Outlook, IMF |

Fortunately, the government and OT resolved their disputes, and FDI is beginning to pick up again in Mongolia. In 2013, former regulation against foreign investment (Foreign Investment Law and Strategic Entities Foreign Investment Law) were repealed (Source: Lehman Law). In 2016, the Mongolian People’s Party, which has a history of friendliness with foreign investment, came to power.

The government worked with the IMF to receive a USD $5.5 million loan in 2017. As part of the deal, the government has implemented fiscal consolidation to reduce government debt, passed a new central bank law, and improved the regulatory framework of the banking sector to increase stability of the financial system (Source: IMF).

According to an entrepreneur who helps companies attract foreign investment, international development organizations, such as Netherland's FMO and Belgium's BIO, have restarted their investment in Mongolia after the IMF deal. (Some major ones, like IFC and EBRD, never really left). Private foreign investors are also starting to come back to the Mongolian market. In fact, in 2017, FDI into Mongolia increased 136%. As a result, Mongolian GDP growth reached 5.1% in 2017, surpassing IMF’s predicted growth rate, shown on the first graph.

Judging by the correlation between economic growth and FDI, and by FDI increasing as the business environment becomes more friendly to it, Mongolia is set to expand very fast. As Oyu Tolgoi prepares for Phase 2 of its project, Mongolia’s economic growth could resemble 2011 peaks in both GDP and FDI.